Larry and Arthur

On the eve of No Kings, two old men and a college boy ask, "How much is enough?"

“Larry and Arthur,” by Finn McNany, launches a series of reported stories on the direct and indirect trickle-down effects of the Trumpocene in the small towns of the Upper Valley, a region of New Hampshire, tilting right, and Vermont, strongly liberal, divided by the Connecticut River.

The writers were students in a creative nonfiction course I taught at Dartmouth College in spring, 2025, called “The Reporters.” The syllabus included this statement: “Students of all politics, or none, are welcome, with the caveat that our project isn’t polemic but reportage, subject to fact-checking.”

The students carried notebooks and asked questions, they read the daily news as reported by others and studied official documents. But we weren’t attempting journalism in the conventional sense, because we took as a premise that journalism in the conventional sense had not been adequate to the challenge of accounting for what it feels like to some people, including this group of young people, to be alive right now. So consider it slant rhyme to the news. It’s not “breaking,” it’s about things that feel to some already broken, and how people keep living anyway.

It is in no way comprehensive or even representative. A better way to understand these young writers’ endeavor is to consider what they read, watched, looked at, and listened to; I’ve posted the first four weeks of the syllabus—or, an essay in syllabus form—starting here. You’ll see that we began not with a newspaper but a poem, “Diving into the Wreck,” by Adrienne Rich, which includes these words:

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I imagined students would be drawn to variations of the news. I thought the work might be explicitly or circumstantially radical, in the sense of seeing what power tells us not to see. Some of it is; and some of it looks inward, or studies the moment at a more oblique angle. Some students consider themselves “political”; some never had; some still don’t. With my students, I learned as we went, especially about some of what it can feel like to have lived half your life with Trump as president or planning his return. Just the way things are.

Which is why we’re launching the series with a story about the way things were. Or, at least, how they seemed to be in places dedicated to establishment power, such as the Ivy campuses where Larry and Arthur studied, and where the author of this piece, a first-year student named Finn McNany, studies now. Finn and I talked about some of it what it meant to begin a series about “now” with a story about two old white Ivy League men by a young white Ivy League man. Consider it the point of departure, from a college, Dartmouth, with a long history of reproducing power for white men, most of them, like these old fellows, Protestants, a good many of them, like these men, generations deep in Ivy privilege.

And then, too, a new point of arrival, since such campuses have in this second Trump administration become frontlines in a contest over the order of power, not a “debate” about higher education but what can fairly be called a federal attack on its current form, “challenging the way we use language,” I wrote in our syllabus, “and what happens in classrooms and who gets to be there.”

Men such as Larry and Arthur have always been here, in the Ivy League, but what’s interesting about these particular men is that in their eighties they still are. That’s where Finn found them. He took as his departure point Trump’s targeting of public library funding. Finn decided to investigate in our local public library, only to discover that the destruction of old orders is fast and slow at the same time. The threatened library, according to the librarians with whom he spoke, is for now still just the library. Full of books, none of them yet banned.

One day he got to talking to an old activist, who found one on the shelves she wanted him to read: Going After Cacciato, Vietnam veteran Tim O’Brien’s magical realist anti-war novel, about a grunt in Vietnam who goes AWOL, who rejects the war by walking away from it. That’s one option. She also had some people with whom she wanted Finn to talk: the senior citizens who every Friday gather on a street corner at the edge of campus to protest. That’s another option.

Protest what? “We have these concerns,” these two old men tell the young man, who writes of his own questions, “I pressed because I’m desperate.” For options, yes, and for context; for history; to know what he has been given and what he might return. How much is enough.

—Jeff Sharlet

Larry and Arthur

By Finn McNany

We agreed, over email, to meet on the corner. The same corner we had met on at the demonstration.

The demonstration was a protest, organized by the Upper Valley Democrats of New Hampshire and held on the intersection of Main Street in the college town of Hanover. It’s the intersection where Dartmouth College meets the outside world.

The sky was grey on the day of the demonstration, and raindrops fell occasionally. There were around 60 people, split evenly among the four corners. Most of the protestors had white hair. Some had grey.

Larry has white hair. Arthur has grey. Larry held a sign that said, “We are all Mohsen Mahdawi now,” the Palestinian Columbia University student who was detained by immigration officers—plain-clothed, armed, masked individuals. Arthur held an LGBTQ+ flag. I met Larry when I walked up to him and asked why he was protesting.

He looked dumbfounded. “Do you know who’s in office?”

He said that they were taking people off the streets with no judicial process. “They could take me or you or anyone.” I didn’t know if I believed that. I knew federal agents were seizing undocumented people, that teams had snatched up international students in New York City and near Boston, and that Mahdawi had been shuffled into a black SUV when he reported for what he thought was a citizenship interview. But would they really take me? A white citizen with no particular political record? For what?

I asked Larry how long he had been protesting. “I could say eighty-five years,” he started, “and I’ll be eighty-six next month.” He was convinced I’d been pulling his leg with my first question. He introduced me to the man next to him. “This is my friend Arthur. I’ve been getting him to come to more of these events.” Larry wore a blue button-down. Arthur wore a fleece coat. They protest here every Friday.

The drivers who honked often waved to the people on the corner. I asked Larry if they had ever had any dissenters at the intersection; he said he hadn’t noticed any. Trump had lost New Hampshire by less than two points, but Hanover went for Harris by 85%, more than any other town in the state.

I asked Larry if it was valuable to protest in a place where people agree with what you’re saying; I thought the point was to change minds. Was that happening here? He told me he’d done work in the more rural parts of the state, where there are towns nearly as politically lopsided. Those people didn’t often agree with him. He thinks both kinds of activism—reaching out, and reminding the already-persuaded to stay strong—are valuable.

I asked again why he protested here, specifically on the intersection we stood at as rain drops stained the crosswalk beneath us. “We protest here because it’s close.” They came to the intersection from a retirement community on the edge of town. Larry gazed at the cars driving by. “And because we can.”

∗ ∗ ∗

A month later, Larry, Arthur and I returned to the corner.

Arthur arrived first. He stood with his hands in his pockets and a distant look on his face, staring into traffic. I waited on the other side of the street, unsure if he would recognize me.

The light turned and I crossed. I greeted him with a smile and shook his creased hand.

Larry approached from behind, sneaking up on Arthur with a sly grin and tapping him on the shoulder. The two were here because I had asked to talk more.

“Should we head to Umpleby’s?” Larry asked us, turning on his heel and starting back down Main Street. Arthur and I followed Larry to the coffee shop. He had an odd gait, his left leg swinging out awkwardly to the side. Arthur moved with a slow, shuffling step. I was ready to offer him my hand when we stepped off the curb to cross the street, but he didn’t need it.

Inside, Arthur picked a table tucked into the corner. The old men sat next to each other, across from me; Arthur on the left, and Larry on the right. Larry removed his blue baseball cap, and the two waited, eager. We knew we had roles to play. They were the old men, thinking about how they had tried to live honest lives, and I was the young man, trying to figure out how to live his.

Arthur had returned that morning from Cambridge, where he had gone to visit friends. One of them was a Chinese woman raised in Hong Kong who worked in Harvard’s School of Public Health. She was around forty, he thought, “but she never completely pinned down her green card. Now, she’s worried.” President Trump’s mass deportation plans were accelerating; That month saw more ICE removal flights than any previous month. Trump had not yet sent Marines into Los Angeles then, but he had promised “the largest deportation operation in the history of the United States.” When Arthur spoke, he looked down. My eyes were level with the crown of his head; his silver hair.

The two men worried, reading the news, about the future of Harvard, of which they were both alumni. They had read about the government taking back billions in grants and about President Trump’s plan to bar the school from enrolling international students. The New York Times had reported White House conversations about “toppling a high-profile university to signal their seriousness.” Arthur went to Harvard for undergrad, and Larry had earned a doctorate in education there. Arthur was a PhD, too, in economics. Arthur and Larry believed in higher education.

Arthur was a third-generation Harvard grad. His grandfather became a professor, his father had been a high school teacher, and an engineer.

Like Arthur, Larry was from Massachusetts, where his family had lived for generations. At Williams College in the late 1950s, he’d studied American history and literature and learned about the Civil Rights Movement and what was then called third world development. He deviated from the path that his father, a third-generation owner of a family dry cleaning business, had expected. Larry didn’t want to spend the rest of his life handling dirty laundry.

Arthur studied political science. He didn’t decide he wanted to actually work in government until his senior year. All he knew was that he didn’t want to do what his classmates were doing.

Arthur smiled. I studied his hearing aid; its silver wire snaked out of his left ear and curled up and over the top of it. “I really was confused, but it was just at that time that Richard Nixon was traveling in South America.” In 1958, Vice-President Nixon went on a tour of South America. In Caracas, Venezuela, his motorcade was attacked, the car kicked and spat on. This treatment of an American official shocked Arthur. He felt compelled to address the economic and social needs of these foreign countries, to offset the hatred these people felt toward the U.S. The event helped Arthur find his path. “I sort of thought, you know, maybe what I would like to do is something internationally that could be pleasant, meaningful.” He rested his chin on the palm of his right hand. “And, in those days, Larry and I, we graduated in a time when we actually thought we could go abroad and do something useful and meaningful.” Larry smiled at his friend from behind his wire rimmed glasses.

I’m confused about what to do next: law school, teaching, or writing, maybe. I wish there was a Nixon, an international incident, that would help me figure out what to do with my life, too.

Arthur won a grant from the Ford Foundation which positioned him in the United Nations office in Dar es Salaam, in present day Tanzania. Tanganyika at the time, in 1964. Arthur’s year abroad convinced him to “carry on,” and he did, working for the UN until retirement. He worked and raised his family in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Fiji, Sudan, and China.

I asked when Arthur and Larry had met.

“You could say we formally met when Arthur kicked the shit out of me, in football.”

Arthur took over. “I was a crashing fullbacker, he was a linebacker. And my job as a fullback is if you can’t get around him, you walk over him and kick through.” Larry leaned back, enjoying the routine.

Arthur and Larry had been prep school boys. Arthur had attended Milton Academy—among its alumni are T.S. Eliot, multiple Kennedys, and James Taylor—and Larry went to Noble and Greenough School, whose graduates include Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Henry Cabot Lodge among others. Prestigious rivals just outside of Boston. Besides possibly smashing into each other on a football field, they didn’t meet until they shook hands five years ago at Kendal, a retirement community in Hanover. Arthur is bigger than Larry, or at least he was. It’s hard to imagine them playing football now.

Larry had also been funded by the Ford Foundation. He had applied to the Peace Corps almost as soon as it was possible to apply, in 1962, just after Kennedy announced its inception.

I felt like I was talking to knights, nobles from a different time, raised and taught to serve. Now, we are watching the international order they served crumble before our eyes.

Larry laid out his timeline, looking up at the white ceiling to remember it all. He graduated from Williams in 1962 and then taught in Hawaii for a year. With the Peace Corps he travelled to Nepal where he lived and worked for two years. He returned and taught in West Virginia to gain the experience needed for his Harvard doctorate. That doctorate program was placing people in advisory positions abroad, which is how he ended up back overseas in Papua New Guinea, dealing with what he called “issues of independence.” He condensed time into a string of neat sentences; years of work summed up in minutes.

Larry paused and Arthur started speaking again. The two were reverential, taking polite turns.

Arthur talked about how the Peace Corps is currently trying to build up their staffing in foreign nations, how there are lots of available jobs. I think he wanted me to work overseas. I think if he could, he would have everyone work overseas. Larry stopped him. He was hungry.

While he ordered, Arthur talked more about prospective jobs which entailed helping out remote communities in distant nations. He folded and unfolded his big hands. His nails were well-kept, and his blue veins visible beneath his skin. “I just wanted to make that point,” he said, turning to me, “that while it may be different today, than it was in our day, nevertheless it can be very meaningful.” Meaningful. It was a word they believed in.

When Larry returned to his seat, I asked why: Why did they do what they did with their lives? Hadn’t they felt pressure to get jobs with higher salaries? In my first year of college, I’m already feeling the weight. Classmates compare internships and connections, and it seems like everyone around me is training to work in finance, to handle someone else’s money; training to get rich quick. There is an unspoken pressure to earn in the top ten percent.

Larry leaned in. “One of the questions, Finn, is how much is enough?” It’s a question that I ask myself a lot; what do I really need? Would that ten percent job solve all my problems?

Larry had deep blue eyes. Arthur’s were also blue, but lighter.

A waitress brought over three iced coffees and a croissant. Larry continued talking. “Both of us live lives that are, I would say, calling-led. Led by a sense of calling, that were not driven by a desire to make money, at all.” He went on, like I didn’t believe him. “And now, you know, you’ve got to notice that both of us had Harvard degrees, and both of us had good educational backgrounds and all of that. But Harvard degrees aren’t necessary to living a life of commitment.”

Larry recommended a book. One he wrote, with his wife and two other authors. His name happens to be first, because it’s alphabetical. The book is called Common Fire: Leading Lives of Commitment in a Complex World. It’s a study of 100 people who had led committed lives, most of their lives.

“Very often, at some time in their formative years, and your formative years aren’t over yet, w’’re talking about mid-to-late 20s, at some time during that period, they had what we called a formative engagement with otherness. They had met with or had encounters with people who were different from themselves, and whom they came to see as fundamentally human.” Arthur sipped his coffee through a black straw. I wondered if this might be one of those conversations. Although these two men attended prep school, like me, before joining the Ivy league, like me, their age and experience felt like a stark form of “otherness.”

Larry apologized for forgetting to bring a copy for me.

Larry picked apart his croissant with shaky hands. He worked with small movements. Arthur continued to talk about the UN. He stressed a distinction that he and his coworkers made: they always said they were part of the UN, not the U.S.

“Why was that important, Arthur?” Larry turned to face him. He was asking for my sake.

“We had some doubts about some aspects of the U.S. community operations,” Arthur said gently. He spoke in a soft voice. Larry’s was rougher.

“Let me just ask this question,” Larry said, making eye contact with me before turning back to Arthur. “Did you know about or read The Ugly American?”

“Yes, I was aware of it.” The 1958 political novel was written by William Lederer and Eugene Burdick, authors and naval men, disillusioned with the U.S. diplomatic efforts in Southeast Asia. The instant best seller depicted the failure of these U.S. diplomats, whose insensitivity and refusal to accept the culture and customs of nations overseas was in sharp contrast to the far more successful soviet diplomatic efforts.

Larry felt I should know about the book. The Peace Corps, he said, was viewed by Kennedy and his administration as a direct answer to the problems put forward in The Ugly American. Larry knew one of the authors, a fellow Quaker in Vermont. He pulled out his phone to search him up. With his index finger, he typed, one letter at a time.

And while he typed, I talked about the news.

I told them how reading it sometimes made me feel like the world was ending.

How the news suffocates me and makes my chest heavy.

I’ve tried to remedy my fear with research. I told Larry and Arthur that I had been reading local newspaper articles from 1968, to ground myself. I chose 1968 because, according to Google, that was another time when people felt the world was ending.

***

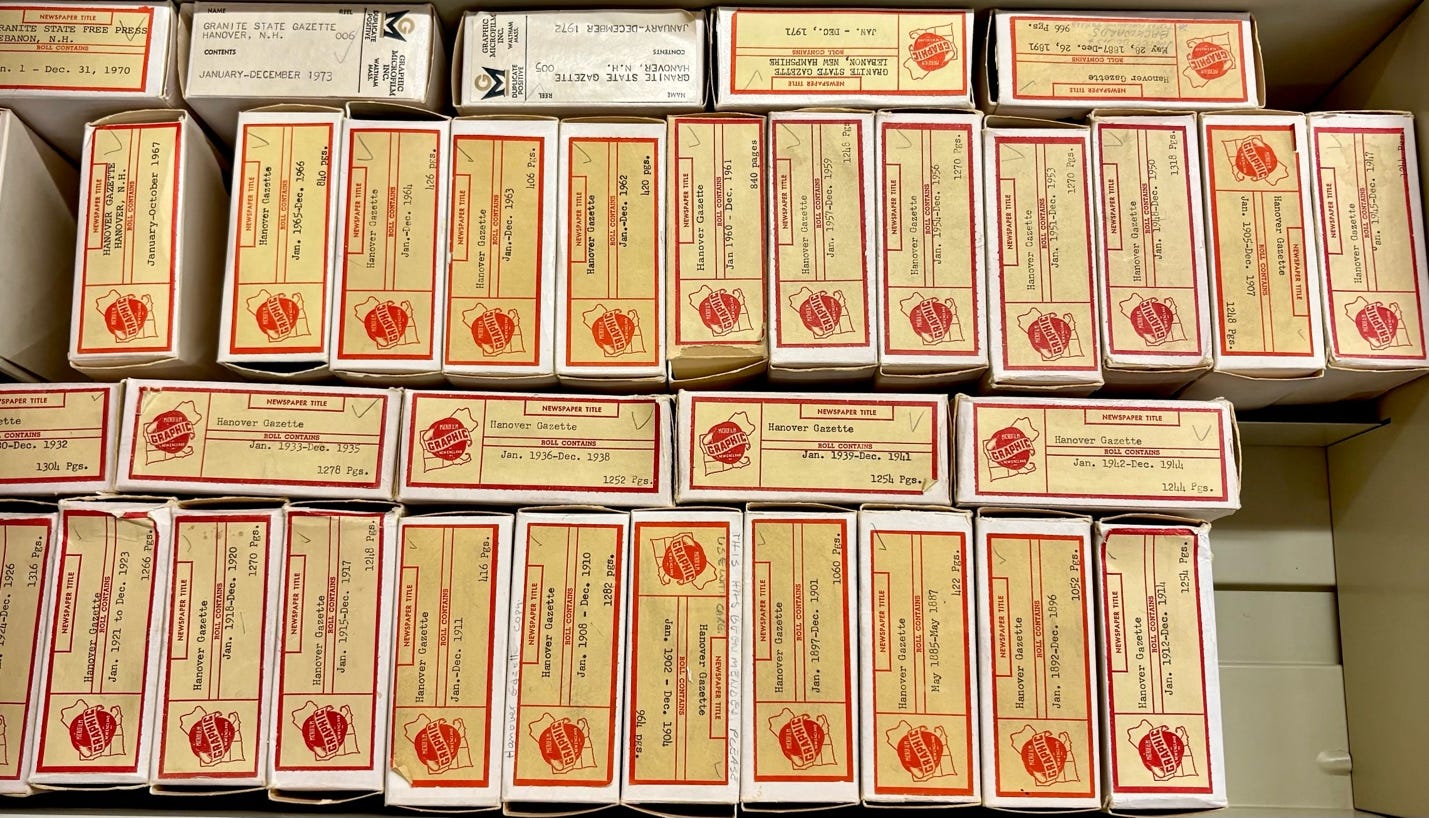

I had discovered these papers, stored on microfilm, at Hanover’s public library. Centuries of history wrapped around spools that fit in the palm of my hand. I made routine visits to read the Granite State Gazette, which was published every Thursday, and sold for 15 cents a copy. In April of 2025, I read the paper from April of 1968. One of these old issues contained a front-page piece from the editor titled, “There is Hope.”

An editor who traveled to Marlborough, New York, to pick up used fonts of linotype matrices ended up touring the home of the man selling him these matrices, for it contained “one of the finest and most complete private museums of Civil War impliments extant.” It was in this museum that he “couldn’t help but muse about man’s inhumanity to man” as he examined rusty bayonets, bullets, and assorted guns. The editor reflected on how the Civil War had been rated by historians as “the most terrible and costly in terms of human lives” of any U.S. war. He wrote that he thought Vietnam might surpass it. Vietnam did surpass it. 620,000 Americans died in the Civil War, 58,000 in the Vietnam War—plus at least a million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed on April 4th of that year, just two weeks before this article was published. The editor wrote how it was “ironic that the death by assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, who preached non-violence, should set off a wave of civil strife across this nation.” He then cited signs of hope, his hope “that man’s humanity to man may eventually lead to peace”: A march on city hall in Kalamazoo, Michigan and a Tri-State Women’s Leaders Conference for Highway Safety at the New Hampshire Highway Hotel Conference Center on May 1.

That was it, a march and a conference.

Maybe we’re just supposed to get used to the world ending.

The paper also tells us that in Lebanon, New Hampshire, “Roger Clark of East Hartford Conn. spent the Easter weekend with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Leon Clark of the Meriden Road,” while Staff Sergeant Neil R. Judd spent his weekend “at a forward base in the Western Pacific.”

This issue was full of ads for items and businesses, including a stainless-steel tub, washing machines, electric heat, Avis cars, Trinovid binoculars, “The Colonial Bookshoppe,” women’s shoes, custom made drapery, the Hoover dial-a-matic vacuum, speed reading lessons, and the same co-op grocery store that’s here today.

The National Bank of Lebanon advertised auto financing with a picture of a young mother, holding her baby. A line of text underneath the image read, “soon Daddy will come home driving our brand-new car!”

Immediately to the left of this ad, the paper reported the death of Aircraft Ordnance 2/C William S. Cutting, the son of Mr. and Ms. Stanley W. Cutting, who was killed near Vietnam. His P-3B anti-submarine aircraft was hit by hostile fire in the starboard wing, knocking out an engine and starting a fire. All attempts to extinguish the flames were unsuccessful. Flying too low to bail, the crew attempted to make an emergency landing at Phu Quoc Airfield. Within sight of the runway, still aflame, they prepared to land their stricken aircraft. As the plane banked left onto its final approach, the starboard wing tore off and the P-3B tumbled into the sea; there were no survivors.

In Orford, New Hampshire “Guy Huntington spent the weekend with his daughter, Mrs. Ila Tillotson, in Williamstown, Vt.” Also, “Forrest and Edwin Pease and Phillip Allen of Alfred, Me., were Sunday dinner guests of Mr. and Mrs. Glenn Pease.”

In Etna, “folks are sorry to learn that the nice black dog belonging to Ethel and Morris Hayes has not been seen since Saturday. They have had this pet for 10 years and will miss it a lot.”

This is the news from 1968.

***

In 1968, Larry was at Harvard. “Harvard had its big march, the one,” he said. “The fist. The Black Fist march.” It was a post-election rally and anti-war demonstration, campaigning for the immediate withdrawal of all troops from Vietnam. It was happening outside the windows of the building where he was taking his PhD oral exams, before he went overseas to do his doctoral research.

He looked at me. “I remember thinking, should I be here or there? Should I be down with the protestors at this moment? Or, should I go ahead and finish my doctoral work?”

At the demonstration on the corner, he had expressed frustration that more Dartmouth students weren’t standing outside with signs, voicing their support. I asked if he thought the two situations were similar.

“Maybe it is similar,” he started. “I was absolutely sympathetic of course, at that time.” He had weighed his options of immediate action or later work he believed could be more valuable. “It was a matter of choices between importances.” He’d stayed inside and taken his exams.

I asked if he had faith that people are making the same decisions now.

“I wish I could.” I watched his blue eyes through his glasses as he spoke. “You know better than I do, Finn.”

He said it with confidence, but I’m not sure that that’s true. I like to think that that they are, that people are making decisions they believe will have the greatest positive impact on our collective future, but I’m not sure that they do.

There are different pressures, he thinks. In the Sixties, he told me, you never worried about coming back and not finding good work. Arthur nodded. People studied sociology and the humanities. Students weren’t studying business and IT.

“That’s what everybody does now.” He set his hand down on the table, hard. “Well, what the hell do you learn about the world when you’re studying business or IT? About the real world?”

Arthur looked at Larry and brought up “fear.” A legitimate fear and concern, he said, that students have here. The fear that if they are too committed at the corner, and seem to be too politically motivated, it could score against them. “Seventy or eighty of you were arrested a year ago,” he reminded me. He said it twice. (There were 89 arrests of pro-Palestine protesters.)

I’m curious about fear and about pressure.

Larry didn’t go into the Peace Corps to avoid the draft. Others did. The Peace Corps was referred to by some as a “cult of escapism,” for it offered a deferment from the draft, and while serving in the program individuals could delay their military service. “We were, without any questions, I’m speaking of thirty-nine of us who are in that group, were to a person committed to doing the work that we wanted to do.”

“My case was quite simple,” said Arthur. “I got married in ‘63. I saw my Ford Foundation-financed year in East Africa as sort of a honeymoon. And along came our elder daughter, and well that got me out of trouble very fast.” In 1963, JFK signed an executive order that excused men with children from the draft; they became known as “Kennedy fathers.” Arthur and Larry turned to each other and giggled. Arthur said to his friend, “you just weren’t smart enough, man.” He looked at me as if I might not understand what they’d been avoiding. “It was a messy war, by the way.”

I know that it was messy, that it was horrifying. And I know that I won’t ever know the war in its full extent. It will always be summed up in neat, digestible words for me.

Larry told a story. On the 25th anniversary of the Peace Corps, there was a huge gathering of return volunteers in Washington, DC. “There were thousands of return volunteers, and we marched under the flags of the countries we had served because we always saw ourselves as serving the country where we were. We marched across that bridge, in Arlington, and we came to the Vietnam Memorial. Have you ever seen it?” I hadn’t. He placed his hands on the table, molding the air in front of him into the memorial. He pronounced each word slowly: “It’s two great, granite walls. And the names of all of the guys who were killed. And as you walk down the wall, to the crevice at the bottom, the wall gets bigger. And the names pile up, and pile up. More and more and more and more names, carved into the wall.” His hands traced the imaginary walls. “There were three of us together that time, when we visited. We were three volunteers who took off from the Peace Corps festivities and went to the Vietnam memorial because there was a lot of hostility between people like us who were resisting the Vietnam war and people who were supporting it. And especially with the veterans who were coming back. I have to say that I regret some of the hostility that I felt I expressed toward these guys. It was wrong.” He looked up. “But we were who we were. Twenty-five years later, the three of us walked down that path, walked back up, and at the end of the walk there is a statue. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it, but it’s a statue of three guys. Fighters. It was added to the memorial after there was a lot of complaint from veterans that it was too abstract, just to have the names. The three of us got to that statue and just fell into each other’s arms, and wept, and wept, and wept. It felt like a kind of a healing to us, that we knew that in fact we were brothers with those guys, and that we were all, in some sense, victims of a war that nobody wanted.”

He looked down and sucked hard on his straw. His iced coffee was empty.

I said my next question was pointless. Ineffectual. I asked, if they could go back and do it all again, would they choose a different path?

Larry leaned back and looked at the ceiling. The other customer’s voices filled our silence. “It’s an important question, and it’s one that we probably need to ask ourselves a dozen times through our lives. The way I would answer it right now, at this end of my life is, without any question, I feel very good about having been loyal to a kind of inner conviction that I was here, to make a positive difference in the world. That I would never change, or I don’t want to change anyway.” He looked at me. “There are an infinite number of ways you can do that. I can’t imagine doing it the same way another time. He leaned forward. “Life is radically interdependent. Everything we do is connected with everything else. You can’t be obsessed with that, but it’s important to recognize it. At the bottom of that, there’s a kind of a deep joy.”

His answer made me smile. I want that deep joy.

“I mean, for example, growing up now, when anybody who knows the first thing about climate change knows that we don’t have a rat’s chance in hell at getting out of this one. I’ve worked actively for the last twenty years on climate change issues. I’m not doing it because I think we’re going to be successful. I’m doing it because you have to do it. I don’t know whether we’re going to be successful or not. Nobody knows.” He paused, and in a softer voice asked, “what’s the choice?”

I asked if he had read Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. I had just read it for a religion class called “What Matters.” He smiled and put his right hand on his chest. He had also read it in college. The Myth of Sisyphus introduces the philosophy of the absurd, a juxtaposition between the human need to attribute meaning to life and the lack of meaning that truly exists. Camus argues that this realization requires revolt and compares our situation to the mythological Greek figure Sisyphus who was condemned for eternity by the gods to repeatedly push a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll down just as it reaches the top. The last line of the essay reads, “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

“There’s a degree of acceptance,” Larry said. “There are no answers out there. There are no absolute truths. It’s our responsibility to construct a truth that works, for us and for the world. I didn’t mean to get down into that particular set of weeds but uh…” he trailed off.

“What denomination were your parents?” Arthur asked. He meant in Christianity. “What did you grow up in?”

“Roman Catholic,” I said.

“I’m a Unitarian Universalist,” Arthur said

Larry laughed.

“He thinks it’s funny because he thinks that Unitarians don’t know what the hell, which way is up, and which is down.”

“Well, that isn’t quite true,” Larry interjected. “You and I better have some more conversations.” He turned to me. “I was a fifth generation Unitarian. He’s got nothing on me.”

“One of the things that I’m doing at the moment,” Arthur said, “is I have a Substack. It started out on the Middle East situation, but I was being warned not to get too deeply into the Middle East because politics in Washington were so negative about the two-state solution that I could even get into trouble with it.”

Larry looks at his friend. “I don’t want to have to drag this guy away from one of these masked gangs that are kidnapping people, right? I mean it would be ugly.”

I asked Larry if he’s worried about being kidnapped by people in masks. He’s not. But he imagines other people being taken.

He stared across the table. “There are times when I just get angry about that happening, and I want to take these guys who are wearing masks, and I want to rip that mask off and say, ‘Who the fuck are you?’” He ripped an imaginary mask off an imaginary masked man.

He and Arthur laughed. “I’m a bad Quaker, but I get so angry at this happening in this country at this time. And I don’t know who they are, these people. I don’t know who they are.”

They wonder if young people talk about what’s going on.

The ones I know do, in one of two ways. Serious conversations occur hurriedly and jump quickly to new topics like soccer or beer. When they are drawn out, the talks almost always turn to jokes, the humor allowing the words to hang in the air a little longer.

“Perhaps as older people,” Arthur said, “we are more sensitive to what could happen. We don’t have much confidence in the government, and we feel that things in this country are going to be worse; more suffering, more fear, and more difficulty in this country before it gets better. That’s not a good thing to say, but we have these concerns.”

They talk a lot about this—this country, this government, these masked men—in their retirement community. Larry organizes structured conversations. He estimates 60 to 75 people show up to these meetings. About 40% of the 200 members who can still leave their beds. I tried to picture them gathered around tables, engaged in fiery debate, their canes and walkers thrown aside. I imagined Larry, leading from the front of the room, calling out questions as if they were squares on a bingo board.

I asked what they gain from these conversations.

“Well, a lot of them have been activated and gone out on the streets.” That’s Larry’s goal; protests, letters, and calls to congressmen. “If people can’t be activated,” he said, “the system is going to roll over all of us. You know, Arthur and I will be dead in ten years, but you won’t. My kids won’t and my grandkids won’t.”

“So, in a sense, we’re out there for you,” said Arthur.

I asked why it matters. Why the world needs to be a better place after they are gone. I pressed because I’m desperate. I looked at them, sitting very still across the table. “Are you guys hopeful?”

Larry answered, “I think that’s the most important question in our lives. I think that it’s the lifeblood of a meaningful existence.”

We paused.

“Arthur, do you have hope?” Larry watched him.

“I do. Just simply because I believe that if we have hope, we will still feel the fight is worth fighting.”

Larry checked his watch and moved to the edge of his seat. “We need to take off,” he said.

Arthur wants to give me a copy of his memoir, about his career and his life, which he wrote five years ago to leave to his grandchildren. He suggested we meet again, in a week. We collected our things and stood up from our wooden seats. Outside I shook Larry’s hand, and he pulled me in for a hug. Arthur did the same.

Bravo, Finn. That was deep and deep reporting. 10/10, no notes.

Tears are streaming down my face as I finish this...thank you, Finn, for such an articulate piece. Jeff, thank you for implementing such a beautifully creative method to engage the young minds that will be the lynchpin to our future. I look forward to reading more articles!